Novice woodworkers on the path to becoming confident woodworkers must learn the language and lingo to better understand instructions and advice.

Every editorial product is independently selected, though we may be compensated or receive an affiliate commission if you buy something through our links. Ratings and prices are accurate and items are in stock as of time of publication.

Seasonal Wood Movement

For woodworkers, “Seasonal Wood Movement” is a term that is top-of-mind when making any project, so it’s the perfect place to start. Simply put, all solid wood swells when it’s humid and shrinks when the air is drier. This seasonal swelling and shrinking can crack open corner joints and change the structure of wooden furniture. It can also result in cracks or cupping* across the face of a solid wood board.

Each species of wood is different, but red oak, for example, can swell and shrink 3/16-in. over a 12-in. width. That means that a 36-in.-wide solid-wood tabletop could swell or shrink up to a 1/2-in. over the course of a year!

Wood moves as a percentage of the size of the wood, therefore smaller parts move less than large parts. Plywood, which is far more stable than solid wood, was developed to avoid the problems created by seasonal wood movement.

*See “Cup” in slide six.

Hardwood

Most hardwood trees are deciduous trees with leaves that fall off in the fall. Premium commercial species like maple, cherry, walnut and oak are prized as premium hardwoods for furniture making and cabinetry. Ash is ideal for baseball bats and hickory for ax handles. These woods are durable and, predictably, pretty darn hard! On the other hand, some ‘hardwoods’ like aspen, poplar, basswood and cottonwood are quite soft. While aspen and poplar may be used on the hidden parts of furniture, basswood is so soft it is used for carving and architecture models.

Softwood

Softwood are coniferous trees with (pine)cones that keep their needles all year long. All of the lumber 2x4s, 2x6s, etc. that you get at home improvement stores are some assorted variety of fast-growing softwood. Tree families like pine, spruce, hemlock, cedar and fir are all considered softwoods, and each species is unique. Sitka spruce is prized for guitar soundboards, rot-resistant and aromatic western red cedar for use in exterior applications, and lightweight. Then you have giant redwood, which is considered one of nature’s strongest materials relative to its weight! The name ‘softwood’ is definitely a little misleading: dense softwood timbers like Douglas fir and southern yellow pine are actually harder than ‘hardwoods’ like cottonwood and basswood.

Burl

Burls are beautiful and highly figured woods. Easily recognizable on the side of a tree, the burl appears like an unsightly growth. When trees experience trauma, like fungal infection or injury, they respond by aggressively healing the affected area. The tree heals quickly and chaotically, producing an interwoven, knotted dome rather than linear like the rest of the tree. When cut, however, the burl reveals beautiful interlaced dark and light grain that is prized by woodworkers.

Pitch

Also known as sap, pitch is created when a tree is healing itself from injury. The tree sends a thick, dense anti-fungal, anti-bacterial liquid to ward off infection and bug infestation. When the tree is cut down into lumber, pungent pine-smelling pockets of pitch can drip on work tables and build up on saw blades. Pitch is found in coniferous softwoods species like pine, spruce and Douglas Fir.

Cup

Concave cupping occurs in wood for two reasons. Boards that are cut nearer the center of the tree tend to cup or curve more. The moisture and density of the wood is different on both sides and the cup occurs in the initial drying of the wood. Cupping can also occur when a board is exposed to moisture on one side and not the other. As the wet side dries, it shrinks and pulls the sides up.

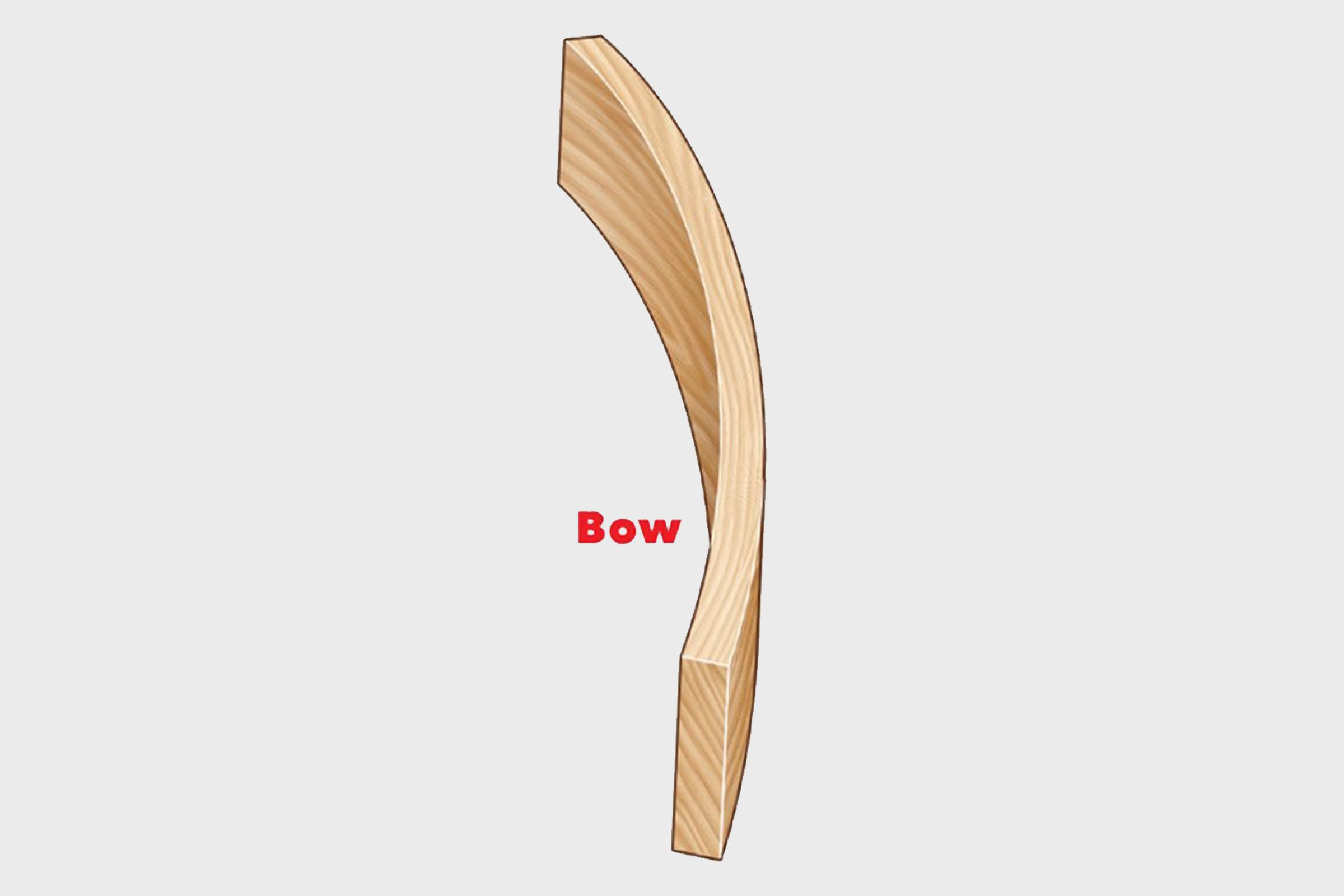

Bow

A board that curves along the face is bowed. Trees are naturally tapered, and while the straightest boards follow the grain, boards that bow are generally cut across the grain. The bow, or curve is a natural expression of the changing grain and the transition from living tree to rectangular lumber.

Warp

When a board is both bowing and cupping, it’s called a warp. These twisted boards are very difficult to get straight and are best avoided. All wood comes off a sawmill as a rectangle, and the tension in the wood fibers twists the board this way and that as it dries. Lumber often warps around large knots, where the grain curls around the area where a tree limb grew. One way to utilize a board like this is to cut it into shorter lengths to diminish the relative curve. You should never run a warped board through a tablesaw.

Wood Grain

Wood grain varies from species to species and depends on how the lumber is cut from the tree. Oak and ash have open-pored wood grain and texture. Other species, like maple, cherry and sycamore, have closed grain which is smoother both visually and to the touch. Flat-sawn lumber is most common and has archetypal arched grain called cathedrals. Alternatively, rift-sawn lumber has a very linear grain, and quarter-sawn lumber exposes reflective rays, as in the white oak of Arts and Crafts furniture.

Face Grain and Edge Grain (AKA Long Grain)

Each rectangular piece of lumber has three distinct surfaces. Face and edge grain, which are also called long grain and end grain. Face grain is the widest part of a board we most commonly see. Tabletops, drawer faces and cabinet doors are all great examples of this. Comprised of linear grain patterns, face grain and the narrower edge grain are the superior surfaces for gluing lumber together to make larger parts.

End Grain

Chop a piece of wood to length and you’ll expose its end grain, the same grain you see when looking down into a stump of a tree. More porous than the long grain, end grain does not hold as well when glued as long grain. End grain porosity also accounts for the fact that it absorbs finish, like polyurethane or lacquer, differently, appearing darker and more concentrated than adjacent long grain. This tonal contrast is used by woodworkers to highlight well-crafted joinery.

Cross Grain

Defining the grain in the direction across a board, understanding cross grain is important in woodworking. Cross grain is more prone to tearing out (chipping the wood while it is being cut with a blade), especially on the back or bottom side of your work piece. Care must be taken to manage tear out while sawing or you can end up with unsightly voids (gaps) where extra sanding or wood filling is necessary. When you aw across the grain, crosscut blades with 60 or more teeth should be used to minimize flaws.